One really neat bonus of being an antiques appraiser is the everyday “show and tell” I stumble into. When people learn that I am an appraiser, they often share with me the story of some precious family heirloom. I sincerely enjoy these encounters because they demonstrate how deeply we cherish the material past of our lives. I also learn a great deal from such artifacts, for personal objects are never exclusively personal; they always contain something of the historical milieu in which they were created or acquired. Take, for instance, the case of a little memento of the Sears National Baby Contest of 1934.

A woman contacted me via Facebook about a small, two-handled cup that was among her mother’s possessions. It is engraved: Sears National Baby Contest/Prize Winner/1934. This object has very little monetary value, less than $20, yet to my mind this little thing is truly a treasure–not rare, not valuable, but a treasure nonetheless. Its richness lies in its backstory.

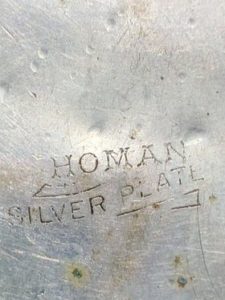

The cup is silverplated, made by Homan Manufacturing Company of Cincinnati, Ohio. Homan was a well-known maker of affordable silverplated items for everyday church and domestic use. The company was founded in 1847 and it went out of business in 1941. The cup is only 2 ½ inches tall and was not expensive. About 10,000 were distributed. I don’t know how many examples still exist today, but families tend to hang on to them for sentimental reasons, so there may be many hundreds of them “out there” in closets and attics. They don’t come up for sale very often, but you may even see a few with the baby’s name also engraved on it, probably added later by the proud parents. Ultimately, these little cups are valued only by their families and generally do not inspire much interest otherwise. But it’s in that “otherwise” part where I think the real value of this object lies.

of affordable silverplated items for everyday church and domestic use. The company was founded in 1847 and it went out of business in 1941. The cup is only 2 ½ inches tall and was not expensive. About 10,000 were distributed. I don’t know how many examples still exist today, but families tend to hang on to them for sentimental reasons, so there may be many hundreds of them “out there” in closets and attics. They don’t come up for sale very often, but you may even see a few with the baby’s name also engraved on it, probably added later by the proud parents. Ultimately, these little cups are valued only by their families and generally do not inspire much interest otherwise. But it’s in that “otherwise” part where I think the real value of this object lies.

“Seeking America’s Most Beautiful Baby”

In 1934, Sears, Roebuck & Co., based in Chicago, held a national Most Beautiful Baby contest in conjunction with the Century of Progress International Exposition, also known as the Chicago World’s Fair, which ran from May 27-November 12, 1933, and from May 26-October 31, 1934. Photos of more than 114,000 babies were entered, vying for a total prize purse of $40,000 in cash, scholarships, and merchandise.

Babies competed in two age categories: up to 2 years and 3-5 years. The entry process began at the state level. The two age-group winners from each state were advanced to the Chicago Grand Prize competition (98 in all) and another 500 from each state formed a pool from which 15,000 “other national prizes” were awarded: 5,000 runners up would receive a copy of their photo enlarged, colored, and framed, and 10,000 more would receive a silverplated cup in an “attractive box.”

Visitors to the Sears Pavilion at the 1934 Fair voted for their favorites and little Marilyn Yvonne Miller of South Dakota won the national Grand Prize, with 24,000 votes. She was awarded $5,000 cash plus a $5,000 “college educational policy” compliments of R.E. Wood, president of Sears, Roebuck and Co.

Let’s Put This Contest in Context

By all accounts, the Century of Progress Expo and the Sears National Baby Contest were both roaring successes, especially so when you factor in what the country was going through at that time. Planning for the fair had begun in early 1928, well before the economic catastrophe of fall 1929. And despite what befell that fall, the fair not only opened as promised, but it even came back for an encore! Take THAT, Depression! Unlike the first Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, the Century of Progress had an intentional forward-looking focus, designed to show a possible future full of wonders and technology and better days ahead. Oh, how the country needed that.

In 1934, average net income was $3,125.42–for those who had any income at all, of course. Only 4,094,420 tax returns were even filed for 1934 (US population was 126.37 million). So if your little bundle of joy could win 5,000 cash dollars . . . well, I don’t even have to finish that, do I.

What I find poignant in all of this is that every one of those qualifying babies had to have been born in the tragic first days, months, and years of the Great Depression, those awful days of shock and anxiety and growing hopelessness. I don’t think this was coincidental on the part of Sears. Rather than lament the precarious time it was to bring a baby into the world, Sears focused the country’s attention on the hope embodied in a baby, nurtured and cherished despite material hardships. Our future. Now our past.

The little girl who won this particular cup was born in 1931 in a small town in Illinois. For her descendants, it brings to life the story of how she won a prize in America’s Most Beautiful Baby Contest when she was 3 years old. That’s a private narrative in a specific family. But for the rest of us, it tells another story, this one a public narrative of the American experience. It’s a tiny thing, and yet it is so much more.

Sources:

Sears Archives, http://searsarchives.com/

Sears National Baby Contest Brochure, https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/ead/pdf/century0208.pdf

“Statistics of Income for 1934,” https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/34soireppt1ar.pdf

Photos courtesy of the owner. Used with permission.