Almost every family has at least one heirloom, “something of special value handed down from one generation to another.” But what does “special value” mean anyway? To whom is it valuable? Is it valuable in market terms (cash) or only in private terms (memory)? What happens when future generations no longer value it?

The word “heirloom” was first used in 15th-century English legal discourse related to wills and probate law. It is, of course, a compound word: “heir” is exactly what we know it to be today, but “loom” at that time meant any tool or implement, not just for weaving. In the days when the family unit was also the primary location of economic production, the “tools” of one’s household assured its livelihood and its future in a very direct way. Our modern use of the term—anything precious that is passed down through generations—did not come into ordinary speech, according to Etymonline.com, until the 1610s.

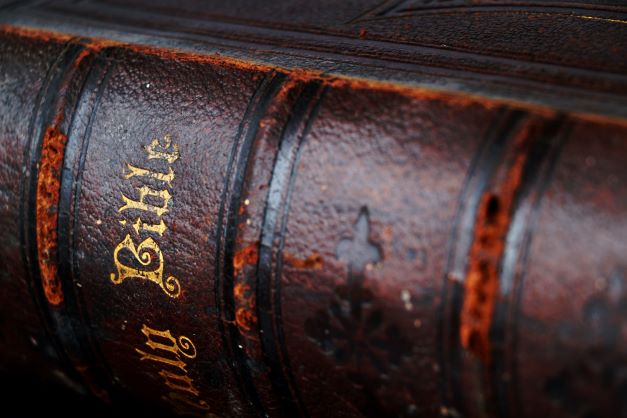

The Family Bible

Let’s take a look at one of the most common heirlooms today, the family Bible: a monumental, leather-bound Bible, often with colorful illustrations and perhaps extravagant illumination (artistic embellishment in the margins or surrounding certain letters). Most also contain pages for recording important events and milestones in the life of the family. The examples I routinely see in the Midwest date to the 1880s or 1890s.

These are indeed very impressive books, but are they valuable? Unfortunately, in almost every case, no. The Bible is the most printed book in the history of humankind. They are not rare, even these massive ones with exquisite decoration. Not only were they produced in huge numbers, but Bibles in general (but especially these) are rarely disposed of for any reason. Thus, the market supply of old Bibles is of biblical proportions, whereas the market demand for them is extremely low.

Most old Bibles have no commercial value at all. The important word here, though, is “commercial.” Heirlooms may or may not be valuable in the monetary sense, which is what makes them so tricky for personal property appraisers. An appraisal is an opinion of monetary value. Sentiment alone has no part in that calculation. So, unfortunately, I have found myself in the tender spot of telling a very sincere, elderly person that her grandfather’s precious Bible, an heirloom, isn’t worth anything.

But of course we all understand that that is absolutely not true! Family Bibles often contain records of extraordinary genealogical value, with lists of ancestors and marriages and births and deaths that are not memorialized anywhere else. Such records make each family Bible truly unique, irreplaceable, and thus invaluable. But its value is limited to the family unit, and even then, it’s the family history, not the book itself, that matters. Without its story, a family heirloom is just another thing.

How to Keep Your Heirlooms Alive

How many times have you come across a photograph in the bottom of an old trunk and you have no idea who any of those people are. Anyone who may have known is either also deceased or can’t see or remember well enough to say. In time, those photos will be tossed out. Or say you find a lovely old pocket watch among Grandpa’s things as you are sorting through his belongings after the funeral. You’d never seen it before and it is engraved with letters you do not recognize. That’s an awful moment because it triggers a decision. Even if you decide to keep the watch simply because “it was Grandpa’s,” in time it will come to mean less and less to his far-future descendants who never met him and (like you) do not know anything about the meaning of the watch. Like the old photos, it will eventually be tossed or sold. The heirloom dies.

So how do you keep an heirloom alive? Firmly plant it in the ground of your family. Identify the people and locations in photographs. Date anything you can. Write out each thing’s story. This requires conversations with elders and some research effort, but it will assure the future of your family’s past.

You don’t need any special skills to do this, just some time, care, and a plan for passing the information on along with the special object. Today, there are cloud-based services that can help. One such company is Artifcts.com. According to its website, Artifcts “offers a secure place to preserve the history, memories, and life experiences behind the objects of your life with images, audio, video, and text. With Artifcts, you can create a dynamic and shareable collection as unique as you!” Remember, your descendants are digital natives, and they are the ones you save your heirlooms for. Don’t resist technology and risk losing your treasures to time and decay.

Which brings me back to the dilemma of the family Bible, which has no commercial value and may be mouldering to dust even as we speak. What do you do with it when restoration is too costly to even contemplate? Is it worth keeping? Not really. Not the book, that is. Capture its stories. Transcribe all of the handwritten notes and lists and other family history recorded in its pages. This is harder than it might sound. Archaic handwriting and premodern inks can be very challenging to read 150 years later. Take your time and cherish the activity. Turn every single page looking for scraps of paper or notations you would otherwise easily overlook. Then, rather than throw it away or burn it (which people are very loathe to do), consider an interment ceremony. Gather your family, wrap it in a clean cloth, and bury it, let it go, solemnly and respectfully.

###

I’d be interested in your thoughts on preserving or releasing family Bibles. Leave a comment or email me at CarolynLawAntiques@gmail.com.

Photo: Pierre Bamin on Unsplash.com