A few months ago, I posted a piece on this blog about my “appraiser’s toolbox,” in which I laid out the essential equipment of my trade. Today’s post is a sort of supplement to that, focusing on the essential skills and, perhaps more important, the essential habit of mind of an appraiser. First, an appraiser must develop the skill of intentional looking, and second, an appraiser must be constantly hungry to know more about things.

A common misunderstanding about appraisers, partly the fault of the Antiques Roadshow, is that an appraiser can simply look at a thing with her naked eye and somehow just know what it is, its life story, and what it’s worth. Indeed, years of firsthand experience and formal or self-education certainly make an appraiser more knowledgeable than the average Joe, especially those of us who have a specific subject area of expertise. For example, as a sterling silver specialist, I can look superficially at a silver object and say quite a lot about it off the top of my head, without additional research or intensive examination. But that only scratches the surface. Even for objects I superficially recognize, it is only by intentional looking that I can truly understand what a thing is and what a thing is worth relative to others like it. And that, in a nutshell, is the appraiser’s job.

As for the essential habit of mind, an appraiser who is not temperamentally curious will be neither very good at appraising nor very happy in the business. As a generalist personal property appraiser, I am thrilled when a client approaches me with some object that’s outside of my knowledge base. Every assignment becomes a learning opportunity.

One of my favorite professional duties of owning my own antiques appraisal business is selecting the continuing education that I’ll pursue each year. For 2021, I knew exactly the program I wanted: Randy Wilkinson’s Wood Identification Workshop. The workshop had been cancelled, of course, in 2020, so I contacted him as soon as I was vaccinated in April asking if it would go forward this year. He assured me that they were on track for an in-person weekend in September and that it would be held at the Mystic Seaport Museum in Mystic, Connecticut. I said, “Sign me up.”

favorite professional duties of owning my own antiques appraisal business is selecting the continuing education that I’ll pursue each year. For 2021, I knew exactly the program I wanted: Randy Wilkinson’s Wood Identification Workshop. The workshop had been cancelled, of course, in 2020, so I contacted him as soon as I was vaccinated in April asking if it would go forward this year. He assured me that they were on track for an in-person weekend in September and that it would be held at the Mystic Seaport Museum in Mystic, Connecticut. I said, “Sign me up.”

As I invisioned my appraisal business in the past few years, I knew that silver would not constitute the majority of it. In fact, in 2021 I’ve been asked to appraise clocks, a 19th-century bedroom set, a Grand Rapids-made tea wagon, and a fireplace mantel/surround, all wooden things. That being the case, I knew this year I wanted advanced training in wood identification and there’s no better teacher than Randy Wilkinson, partner and master conservator at Fallon & Wilkinson, Baltic, Connecticut.

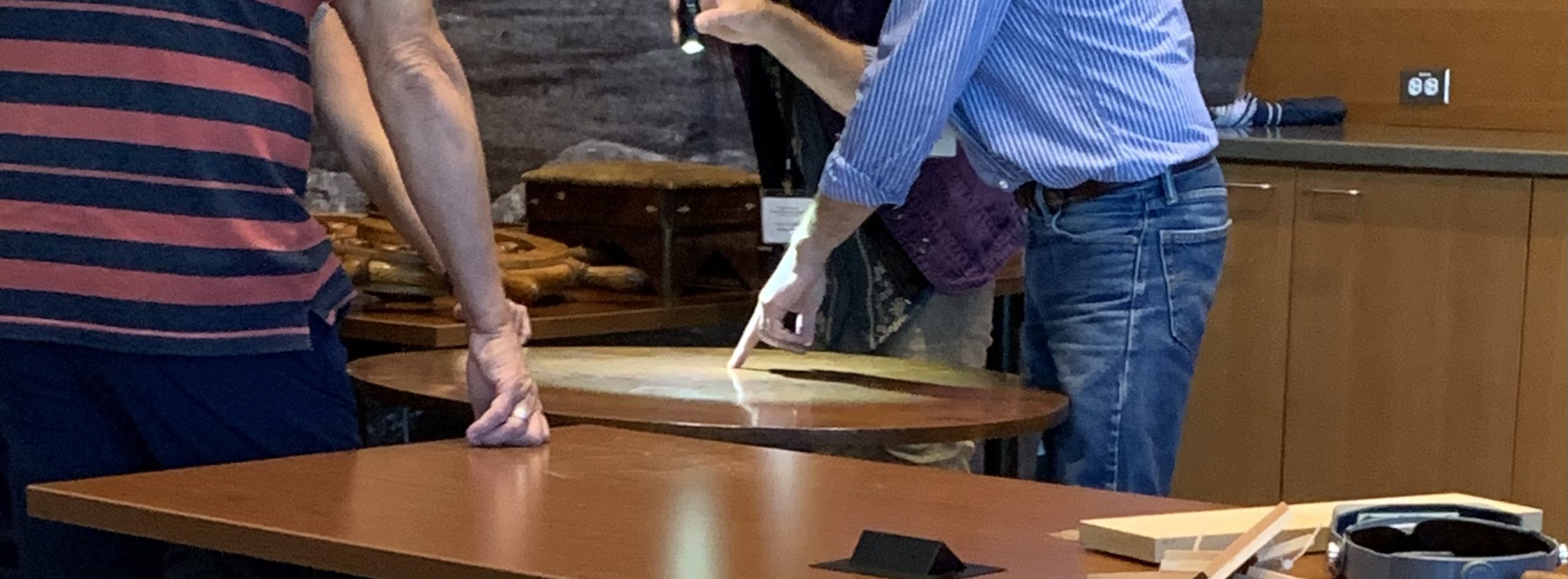

Randy’s Wood Identification Workshop is unique in the United States in that it offers hands-on instruction in the macroscopic and microscopic techniques of wood identification at the cellular level but then also applies those techniques to the practical examination and identification of finished objects, the kinds of things antiques appraisers and dealers encounter virtually every day.

But wood anatomy, cell structure? Don’t antiques people just know one wood from another by looking at a lot of wood? Generally speaking, yes, most people can detect oak from other woods, for example, by experience, but which oak is it? Red or white? The truth is, wood species cannot be identified definitively by surface examination alone. Then add on a couple centuries of smoke, dirt, cleaning products, paint, finishing and refinishing, and it may become virtually impossible for anyone to distinguish one wood from another except under magnification. With magnification, the cell structures of wood may be discerned, and cellular structure is diagnostic.

For professional appraisal practice, the implications of science-based wood identification are tremendous. Definitive wood identification can help to place an object in a geographical region of origin. It may provide evidence for attribution to a specific maker known to work in a particular wood. It helps to expose fakes and also to spot otherwise honest repairs or restoration that may affect value. It may support or refute the provenance of an individual piece.

For professional appraisal practice, the implications of science-based wood identification are tremendous. Definitive wood identification can help to place an object in a geographical region of origin. It may provide evidence for attribution to a specific maker known to work in a particular wood. It helps to expose fakes and also to spot otherwise honest repairs or restoration that may affect value. It may support or refute the provenance of an individual piece.

On Day 1, Randy summarized what we were about to learn: “Wood identification is the recognition of patterns.” I call that intentional looking, knowing not only what to look for but also how to look for it and then how to interpret what one sees in the context of known others.

I had an amazing experience at the 2021 Fallon & Wilkinson Wood Identification Workshop, where I met many wonderful people–conservators, curators, appraisers, auctioneers, and artists. The setting provided by the Mystic Seaport Museum was spectacular. Thank you to MSM for allowing generous access to its historic artifacts, collections, and exhibits. Thank you especially to Randy Wilkinson for sharing his extensive knowledge of wood and practical expertise in a most engaging and enjoyable way.

I had an amazing experience at the 2021 Fallon & Wilkinson Wood Identification Workshop, where I met many wonderful people–conservators, curators, appraisers, auctioneers, and artists. The setting provided by the Mystic Seaport Museum was spectacular. Thank you to MSM for allowing generous access to its historic artifacts, collections, and exhibits. Thank you especially to Randy Wilkinson for sharing his extensive knowledge of wood and practical expertise in a most engaging and enjoyable way.