The other evening (a very cold one) my furnace malfunctioned. It wasn’t a catastrophic breakdown, but it did require an emergency call to the HVAC guy. When he arrived and asked, “Where’s your thermostat,” I escorted him directly to the unit on my living room wall, all business-like. This was an emergency, after all, and the house was pretty chilly, so I let him get right down to it.

I didn’t reveal to him that I live in a thermostat museum.

My house was built in 1924. When we moved in, a little more than 70 years later, we discovered four thermostats mounted on three different walls in three different rooms. Only one was in working order, the other three apparently vestigial. Now I sometimes like to guide guests around from room to room, narrating the history of temperature regulation technology displayed on my walls.

The history of thermostats (yes, there is one) goes way back to the 17th century, but those were essentially scientific instruments that eventually found some practical applications in industry and research. For our purposes, the first thermostat for ordinary domestic use was offered by Honeywell in 1906.

Since then, the thermostat’s technological development has been straight up! An “onboard” clock was introduced in the 1930s. They became programmable in the 1980s, and by 2007, the humble thermostat had gotten “smart” and took its seat on the internet of things.

All that technological innovation notwithstanding, the basic function of the thermostat remains the same as it ever was: automatic temperature control. In the early 20th century, this was an electromechanical process accomplished through an ingenious application of physics whereby certain metals expand and contract in predictable ways. A laminated sandwich of two such metals, variously sensitive to temperature, in a coil or strip, are attached to a vial of mercury such that when the coil contracts in one direction to the specified temperature target, the mercury vial tips (aka the mercury switch), thus tripping the furnace off or on accordingly.

So back to my house. The oldest example in my collection (a White-Rodgers Type 214) is in the foyer near the kitchen entry and doorway to the basement. The White-Rodgers Company was formed in 1937. It’s a real beauty with a dramatic coil exposed atop its no-nonsense metal casing. Then, probably in the late 1940s, a new thermostat was installed in the dining room, this one much more conscious of its domestic surroundings. Its creamy Bakelite casing is softer, rounder, and notably less industrial.

So back to my house. The oldest example in my collection (a White-Rodgers Type 214) is in the foyer near the kitchen entry and doorway to the basement. The White-Rodgers Company was formed in 1937. It’s a real beauty with a dramatic coil exposed atop its no-nonsense metal casing. Then, probably in the late 1940s, a new thermostat was installed in the dining room, this one much more conscious of its domestic surroundings. Its creamy Bakelite casing is softer, rounder, and notably less industrial.

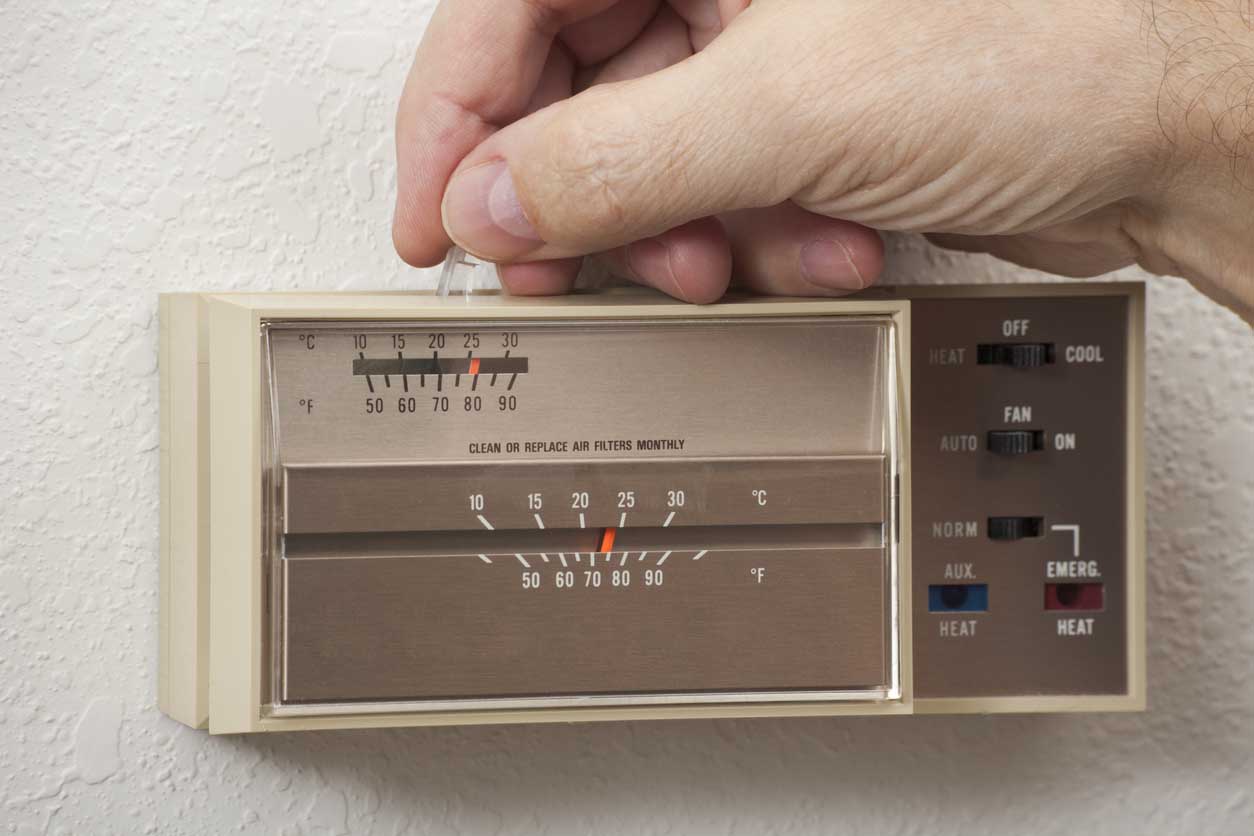

When we moved in at the very end of 1995, the furnace was controlled by an uninspired, plastic box thermostat in the living room, but curiously it was right beside an iconic Mid-Century Modern dial-style thermostat, c. 1960s. In 2008, we finally replaced the old oil-burning furnace for clean, efficient, natural gas and upgraded the thermostat to an eco-friendly digital wonder. Regrettably, we sensibly installed the new one over the others’ existing holes in the living room location and our sensible furnace man sensibly carried them away. Alas, how I wish now we’d kept them in situ to complete my exhibit!

When we moved in at the very end of 1995, the furnace was controlled by an uninspired, plastic box thermostat in the living room, but curiously it was right beside an iconic Mid-Century Modern dial-style thermostat, c. 1960s. In 2008, we finally replaced the old oil-burning furnace for clean, efficient, natural gas and upgraded the thermostat to an eco-friendly digital wonder. Regrettably, we sensibly installed the new one over the others’ existing holes in the living room location and our sensible furnace man sensibly carried them away. Alas, how I wish now we’d kept them in situ to complete my exhibit!

Why would the previous owners leave an old thermostat on the wall? Why install a new thermostat in a different location? My guess is mercury! Old thermostats contain mercury, an extremely hazardous but very rolly-polly material, perfect for electromechanical thermostats but not so much for human contact. Mercury thermostats should never be thrown out in the residential trash. Many municipalities have special disposal sites, but I would be reluctant to even handle one, which is why I believe previous owners of my house decided to leave them “as found,” as they say. Like asbestos, “do not disturb” is the most cost-effective strategy for living intimately with a deadly substance, but when it must be handled, call in a professional.

Whatever the reason these thermostats survived on my walls, I’m delighted that they did. I like to be reminded of my home’s material past. The thermostats are tangible evidence of this building’s own story, independent of me, sharing its 100 years of technology, innovation, and industrial design.